An Archbishop For Our Times

- Peter Carolane

- May 15, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: May 20, 2025

In just eight days, the Anglican Diocese of Melbourne will gather for its Synod, facing the crucial task of electing the next Archbishop. This is a moment of profound significance, a time for deep reflection and for prayer, as the diocese discerns the leadership needed for the years ahead. One of the inherent challenges in such a process lies in breaking free from recent memory and considering the breadth of possibilities for what an Archbishop can be. Our last Archbishop served for a considerable eighteen years, and while dedicated, the leadership styles of the past three Archbishops have perhaps settled into a certain pattern.

For many, the dynamic era of David Penman, who tragically died in office, might feel like ancient history. I can still vividly remember when, in grade six chapel, our chaplain, Brian Porter, prayed for Penman’s recovery after his heart attack. His death was a particular loss because he was a true game-changer, demonstrating a different mode of leadership that much of the current Synod demographic may not fully recall.

In reality, the Archbishop has considerable scope to shape their leadership, adapting it to the specific setting and evolving needs of the diocese. As someone who spent considerable time in the archives during my doctoral studies, delving into the lives and ministries of Melbourne's past clergy, archdeacons, and bishops, I encountered a fascinating array of leadership approaches and characters, starkly different from what I'd witnessed over the preceding four decades. Our first Bishop, Charles Perry, seemed to regularly ride around the diocese on a horse, visiting parishes. The next Bishop, James Moorehouse, was more of a society intellectual, giving hugely popular public lectures in the Melbourne Town Hall.

Given that most Melbourne Anglicans would struggle to name even recent Archbishops, I thought it might be illuminating to glimpse the diverse styles of those who have held this significant office.

***

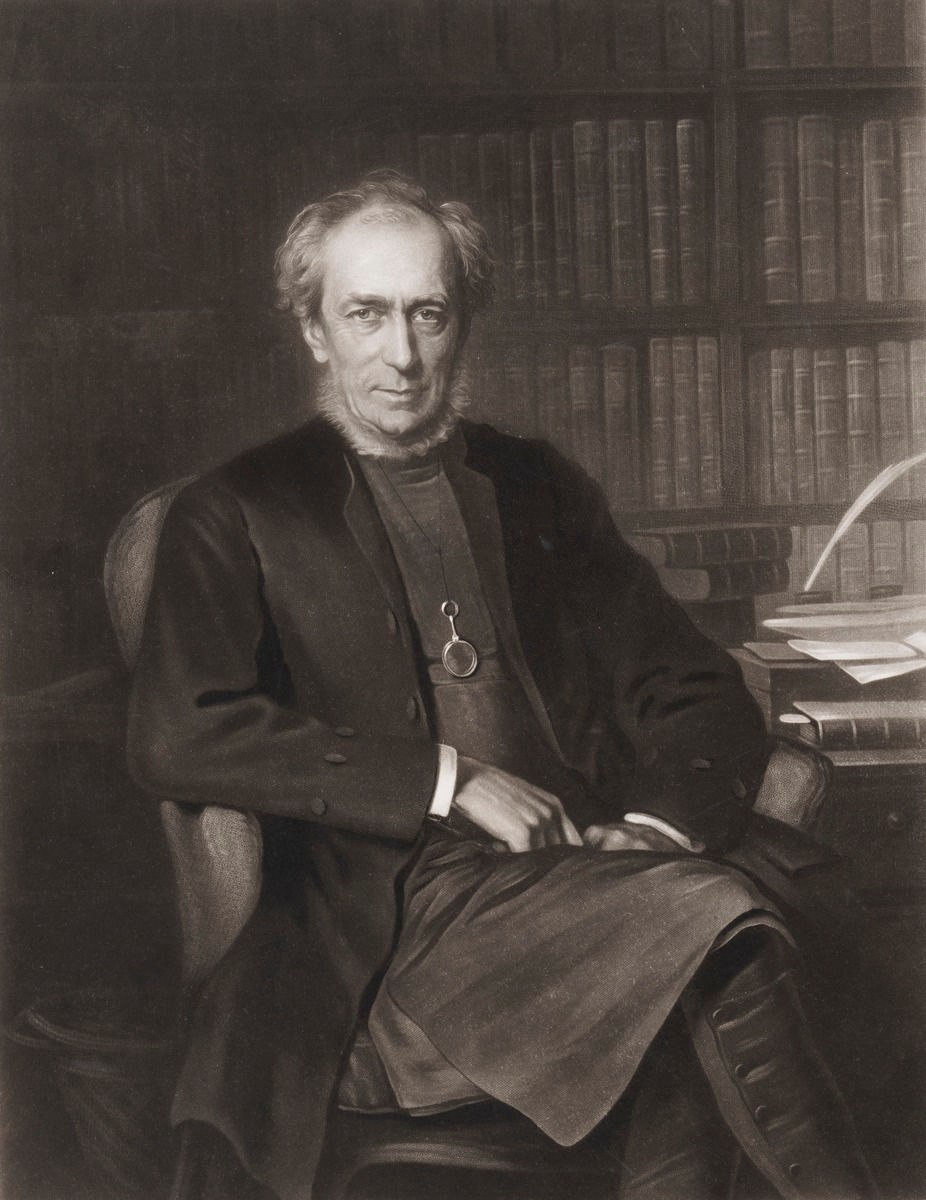

As the first Bishop of Melbourne, Charles Perry arrived in a rapidly growing colonial outpost tasked with building a diocese from the ground up. Consecrated in 1847, he found a vast territory with just three churches and three clergymen. A man of considerable intellect and administrative skill, he quickly set about establishing the foundational structures of the church, advocating for self-governance and overseeing a dramatic increase in clergy numbers; by 1871, his diocese boasted 167 churches and 173 other places of worship. Perry’s evangelical convictions were deeply held, sometimes manifesting as a stern adherence to doctrine. Yet, he possessed the foresight to empower the laity in the church's governance, notably inviting lay people to share in the governing of the church, an independent action praised by many. He also oversaw the establishment of many new mission agencies, including the local outreach to the Aboriginal, Chinese and Jewish peoples across Victoria. He travelled across the diocese with tireless labour, preaching in new places and organising movements to prepare for future growth, proving worthy of his important position during the remarkable population influx of the gold rush era. Despite his strong opinions on matters of worship, including church music, Perry admitted to having no ear for music, a curious trait for someone who legislated on its use in services.

James Moorhouse brought a distinct energy to the role of Bishop of Melbourne, arriving in January 1877 and serving until 1886. His contrasting churchmanship to his predecessor fostered greater theological and practical diversity within the diocese. Born in Sheffield in 1826 and educated at St. John's College, Cambridge, where he graduated as thirty-sixth Senior Optime, Moorhouse had served in various curacies and as a vicar in London before his appointment to Melbourne. Known for his eloquence and intellectual vigour, Moorhouse fully embraced the broader public life of "Marvellous Melbourne," which was then a city experiencing significant growth and prosperity, becoming the richest city in the world. He was a vocal champion of tolerance and reason, favouring open dialogue over doctrinal disputes and actively defending the Christian faith against contemporary challenges like unbelief and secularism, famously advocating for a "candid and charitable method of proclaiming the truth." His preaching attracted large congregations. He was known for his liberality and avoidance of theological partisanship, preferring to focus on common ground among Christians. His engagement extended to practical matters; during a drought, he notably expressed disapproval of prayers for rain if no efforts were made to conserve existing water, a stance that predated significant irrigation works. Deeply committed to elevating the standard of local clergy education, he established the Theological Hall at Trinity College in his first year. Moorhouse was also a highly popular lecturer, capable of filling the Town Hall with attendees, and his lectures on Christianity and Man were widely known. His significant initiatives included launching the construction of St. Paul's Cathedral, with the foundation stone laid in 1880. He was a strong advocate for the admission of women to the University of Melbourne, with Trinity College pioneering tuition for women under his influence. Beyond the pulpit and academic halls, Moorhouse possessed a surprising physical vitality; in his youth, he was a skilled boxer. His impactful ten-year episcopate in Melbourne concluded in 1886 when he was appointed Bishop of Manchester, where he served for another 17 years.

With the funniest name of all the bishops, Field Flowers Goe took the helm during a challenging period marked by economic depression following the land boom, serving from 1887 to 1901. While perhaps lacking the dynamic public profile of his predecessor, Goe provided steady, devoted, and courageous leadership, focusing on consolidating the church's organisation and seeing through the completion of St Paul's Cathedral, a significant undertaking in economically challenging times. He actively combated the growing unbelief and secularism of the era, positioning himself as an intellectual leader in defence of the faith. Though an evangelical, he supported various church activities, even those outside his immediate tradition, notably signing a memorial protesting the persecution of the high church ritualists. He successfully navigated the financial difficulties and oversaw the crucial subdivision of the diocese, a practical achievement in a difficult era. Perhaps his most colourful moments were simply admiring the newly finished cathedral spires. He was appointed one of the select preachers to the University of Cambridge in 1884, a special honour for an Oxford man.

Henry Lowther Clarke was consecrated Bishop in 1902 and then (for the first time in Melbourne) Archbishop in 1905, remaining in office until 1920. He was a firm ruler who steered a middle course through the various parties within the diocese, refusing to be aligned with any single faction. He was deeply invested in improving the training and effectiveness of the clergy and spearheaded a significant expansion of Anglican schools, particularly establishing more options for girls' education. Clarke was also a pioneer in ecumenical relations in Victoria and was not afraid to engage in public controversies, even pursuing a notable defamation case. Despite his significant position and influence, Clarke maintained a surprising simplicity in his personal habits, often travelling to his engagements by tram, train, or bay steamer, carrying his robes in a basket suitcase, a humble mode of transport for the head of the province.

Harrington Clare Lees served as Archbishop of Melbourne from 1921 until he suddenly died from heart disease at Bishopscourt in 1929. Known for his vigorous work ethic and engaging personality, Lees had an attractive pastoral sensibility and was popular wherever he went. He was an excellent chairman of Synod, speaking little but giving decisive rulings, and was not aligned with any particular party within the church. His episcopate saw the undertaking of the completion of St Paul's Cathedral's towers and a significant increase in the social work of the church, particularly through the Mission of St James and St John and the free kindergarten system. Lees was a great speaker, and his sermons, delivered with passion, were so popular that people needed to arrive early to secure a seat at the Cathedral. He also possessed a surprising foresight in communication, being the first Bishop to effectively use the medium of radio for broadcasting his sermons.

Frederick Waldegrave Head (1929-1941) took leadership as the world plunged into the Great Depression, a period demanding practical and compassionate responses. A scholarly yet kindly man, Head focused his efforts on strengthening parochial life through consistent pastoral care, preaching, and teaching. He actively encouraged church societies and social work initiatives, understanding the immense hardship faced by the community, and was a strong supporter of organisations like the newly established Brotherhood of St Laurence. Despite his academic background and establishment ties, he connected genuinely with people from all walks of life. Head's bravery was not limited to his ministry; he earned a Military Cross during World War I as a chaplain, proving he was fearless both on the battlefield and in promoting inter-church dialogue. His life was tragically cut short when he died from injuries sustained in a motor accident while driving to a confirmation service.

Joseph John Booth (1942-1957) was a leader known more for his robust character and practical wisdom than for being a towering theological mind. Described with the straightforward and honest qualities often associated with a Yorkshireman, Booth possessed a strong pastoral sense and was highly effective in attending to the practical needs of the diocese. He was deeply committed to the welfare of his clergy and oversaw the establishment of homes for the elderly, demonstrating a focus on tangible care. His direct and sometimes terse management of Synod was legendary, reflecting his no-nonsense approach. Despite his later success and leadership, he was once excluded from a Master's examination because he hadn't attended enough lectures, a setback that perhaps fueled his practical focus over academic pursuits.

Archbishop Sir Frank Woods (1957-1977) brought a dignified and inspirational presence to the role during significant growth and social change in Melbourne. A highly effective administrator, he responded to the city's doubling population by strategically reorganising the diocese and planning for new parishes. He placed a strong emphasis on the training of clergy and actively sought to empower the laity through new programs. Woods was a key figure in the ecumenical movement, fostering strong relationships across denominations, and was a vocal advocate for progressive social issues, including supporting the ordination of women and a more liberal stance on the remarriage of divorcees. Before his extensive ministry, he served as a chaplain in the British Army during World War II, including time in France and the Middle East, an experience that likely shaped his understanding of human need and resilience. People loved Frank, which is a testament to his charm and leadership.

Robert Dann (1977-1984) holds the distinction of being the first Australian-born Archbishop of Melbourne, marking a significant moment in the localisation of church leadership. He was a strong proponent for progressive change within the Anglican Church, most notably advocating with conviction for the ordination of women to the priesthood, a pioneering stance at the time. Dann also dedicated efforts to strengthening relationships and fostering dialogue with the Roman Catholic Church, contributing to a growing spirit of ecumenism in Victoria. His leadership represented a shift towards addressing contemporary Australian social and theological issues with locally raised perspectives. Despite his later high office, he began his working life as a farm labourer and grocery traveller before studying for ordination at Trinity College.

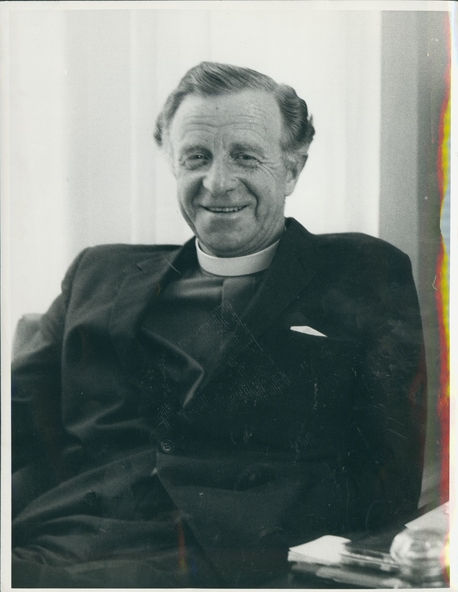

David Penman (1984-1989) was an energetic and visionary leader whose time as Archbishop, while cut short, was marked by rapid change and passionate advocacy. His election in 1984 came after a difficult process for the Electoral Board, where he emerged as the evangelical candidate among others considered. Upon his arrival, he quickly initiated significant structural reforms, creating new departments to focus on evangelism, multicultural ministry, and youth engagement, reflecting a forward-looking approach. Penman was deeply passionate about the church's role in addressing contemporary social issues, from poverty and refugees to environmental concerns and the AIDS crisis. He demonstrated a profound empathy that brought him to tears when facing human suffering. A highly effective communicator, he skillfully used the media to champion causes like the ordination of women. Having served with his family in Pakistan and Lebanon for ten years, Penman returned with a deep understanding of global needs, particularly in the face of disasters. This experience directly informed his leadership in Melbourne, leading him to establish the Archbishop of Melbourne's International Relief and Development Fund in 1988, which would later become Anglican Overseas Aid. Beyond his public ministry, Penman undertook a surprising and highly secretive detour to Iran in an attempt to secure the release of hostages, highlighting his personal commitment to humanitarian efforts. His short but vibrant and productive tenure shows what rapid and significant change is possible when the leader has an audacious vision and the capability to bring change.

Keith Rayner (1990-1999) was known for his intellectual depth, measured approach, and remarkable ability to navigate complex and potentially divisive issues while maintaining unity within the church. He expertly guided the Anglican Church of Australia through intense debates, particularly surrounding the ordination of women to the priesthood, a process that required significant intellectual leadership and careful negotiation to achieve consensus. He also presided over the adoption of a new prayer book and was a committed ecumenist. He completed a doctoral thesis on the history of Anglicanism within the Diocese of Brisbane, providing a deep historical context to his later leadership.

Peter Watson's leadership (2000-2005) was characterised by personal integrity, humility, and a strong, focused commitment to nurturing parochial life and promoting the core gospel priorities within the diocese. He advocated for traditional Anglican liturgy and practice, providing stability in worship. At the same time, he demonstrated engagement with broader social and global justice issues, notably working towards the cancellation of debt for the world's poorest nations. His unassuming and encouraging style was particularly valued in supporting smaller congregations. In a more domestic, yet surprisingly persistent effort, Archbishop Watson unsuccessfully pursued possum control methods at Bishopscourt, proving that even archbishops face relatable, albeit sometimes frustrating, everyday challenges.

Most recently, Archbishop Phillip Freier (2006-2025) was widely regarded as a peacemaker who prioritised reconciliation, particularly with Indigenous Australians. I had the privilege of witnessing Freier launch the Kriol Bible at the Katherine Christian Convention, a testament to the high esteem given towards him by Aboriginal Christians in the Top End. He also championed the safety of vulnerable people and the full inclusion of women in ministry, consecrating Bishop Barbara Darling, Melbourne’s first female bishop. Freier was known for his measured tone for an often anxious church, skillfully fostering unity during challenging times. His leadership extended to advocating for social justice issues and building strong relationships with Melbourne's diverse multicultural communities. Archbishop Freier is fluent in the Koko-Bera Indigenous language, a testament to his deep commitment to reconciliation and understanding of First Nations cultures. In what is perhaps a surprising twist, perhaps even for him, one of Freier's most lasting legacies for our diocese has been the significant rise of church planting. While many factors contributed to that culture shift, I can say from first-hand experience that, especially in the early years of his tenure, while he didn't have much experience with the church planting movement, he had a non-anxious and permission-giving posture. Now our diocese is one of the most active church planting dioceses in the Anglican communion in the West.

***

Looking back at the diverse array of leaders who have served as Bishop and Archbishop of Melbourne, it becomes clear that the office has been shaped by a variety of strengths and approaches. We have seen visionaries who cast a compelling future, entrepreneurs who built structures and initiated new ministries, administrators who brought order and efficiency, academics who defended the faith with intellectual rigour, pastoral figures who cared deeply for their flock, and missional leaders who focused on outreach and engagement with the wider world. Some, like Field Flowers Goe and later Keith Rayner, prioritised maintaining peace and unity among the different tribes within Melbourne Anglicanism, while others, like Charles Perry, Henry Lowther Clarke and David Penman, rose above internal dynamics to push boldly towards a new future. As the diocese faces significant financial and systemic challenges, with many parishes struggling for viability under the weight of compliance, low membership, and a severe shortage of clergy, the task ahead requires more than simply keeping the peace. The next Archbishop will need to be a visionary game-changer, capable of leading the diocese through the changing secular age, demonstrating courage, innovation, and a deep understanding of the complex landscape the church inhabits today.

Comments